Building a Mathematica Package Ecosystem, Part 2.

So a few days ago I talked about building a package ecosystem in Mathematica by extending the built-in package manager. In that post I identified two things that ought to be extended to improve how packages are used in the Mathematica community:

-

The package manager needs to be more automated and paclet servers need to be clearer about what they have

-

Creating and distributing documentation should be more convenient

We had some tools to simplify the first one some. Now we’ll move on to the second.

Let’s start off by acknowledging that Mathematica has a very nice documentation set-up. Every function has a documentation page with usage, details, and examples, related functions, and related guides. It’s pretty high-quality stuff. You can write your own using the Wolfram Workbench Eclipse plugin that is the easy route. Or you could do what I did and rewrite a documentation generator from scratch. The former has many benefits in that it’s:

-

A lot less work

-

Wolfram sanctioned

-

Somewhat more likely to be maintained

The latter has benefits in that it’s customizable and, unfortunately, possible to keep more up-to-date than the plugin, as Wolfram’s documentation format sometimes changes faster than they release plugin versions. But there’s also one benefit that perhaps isn’t as obvious: we can easily extend it to support automatic documentation generation. That last one will be key to simplifying the documentation process.

Automatic Function Documentation

We’ll start by taking a look at what is required to build out decent documentation for a given function:

Extracting Usage Data

Our usage data will simply be the left-hand-side of the OwnValues , DownValues , SubValues , and UpValues . This is all easily accessible. Harder is to then convert this into something readable. The strategy will be all about reducing pattern complexity. There are a few things that will need to happen here:

-

HoldPatternexpressions will need to be converted to their interior expressions -

Pattern,Optional,PatternTest, andConditionexpressions will need to be converted to their left-hand-sides -

Alternativesshould reduce to their first case -

Blank-type patterns should be replaced by their types

The function we’ll need for this will then basically be an extended ReplaceRepeated that handles all these conditions and applies them to the *Values functions. It’s not really worth posting the content of the function itself here, so I won’t.

Extracting Details Data

Our details data will essentially list scrape-able info for general convenience. We’ll want the following:

-

What types of usages a function has

-

Whether a function has

FormatValuesor not -

What

Optionsit inherits from common functions -

What

Optionsit has that aren’t inherited -

What

Messagesit supports

The only interesting thing here is how to determine what Options are new to the function. But even this isn’t hard. We simply take a list of functions from which Options are commonly inherited and just look at Options names intersections one by one.

Configuring Examples

This is a more interesting problem and one that I haven’t yet fully figured out how to handle. Something that makes this tough is that we obviously generally can’t tell what a function will do before we test it, so passing it naive examples could have disastrous consequences. My answer to this was to provide a sample example for each distinct usage which would be left unevaluated. This means we have a new pattern-reduction problem on our hands. This time we’ll apply the following set of rules:

-

Untyped (i.e. without a

Headspecified)Blankpatterns reduce to 0, 1 or 2 symbols, depending on the type of blank pattern -

Typed

Blankpatterns reduce to 0, 1 or 2 objects of theHead, depending on the type of blank pattern -

PatternTestgenerally reduces to the left-hand-side, except when a known type-test is on the right-hand-side, in which case it reduces to that type as many times as the left-hand side specifies -

Patternreduces to its right-hand side unless its right-hand side is aBlank, in which case it becomes the pattern left-hand side as a symbol -

Optionalbecomes its optional value -

Alternativesbecomes the first alternative

Note that these rules could be extended yet further. They just provide a nice starting point.

Finding Similarly Named Functions

With all that in place we’ll lastly want to auto-determine what functions are similar to our function by name, taking advantage of the camel-casing that is the default in Mathematica. In general we can assume that a function that shares the first “camel-hump” with our function is related enough to note. On top of that we’ll want to only use functions that are in the same context, as functions in other contexts are not obviously related.

Sample Page

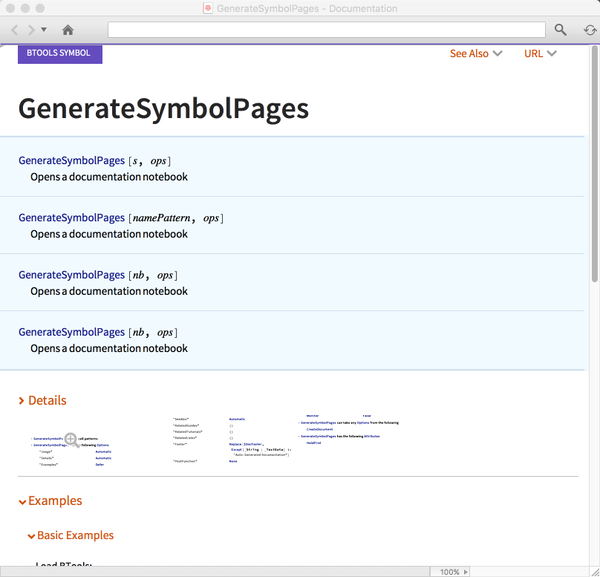

We’ll generate a page for the function that does this itself:

GenerateSymbolPages@GenerateSymbolPages

(*Out:*)

The weakest point of all of this is the examples, but on the other hand it takes only a few seconds to generate that page (and only that because of inefficiencies in over-calling the front-end). That’s significant savings, particularly for someone like me who’s not sure what functions, if any, others will find useful.

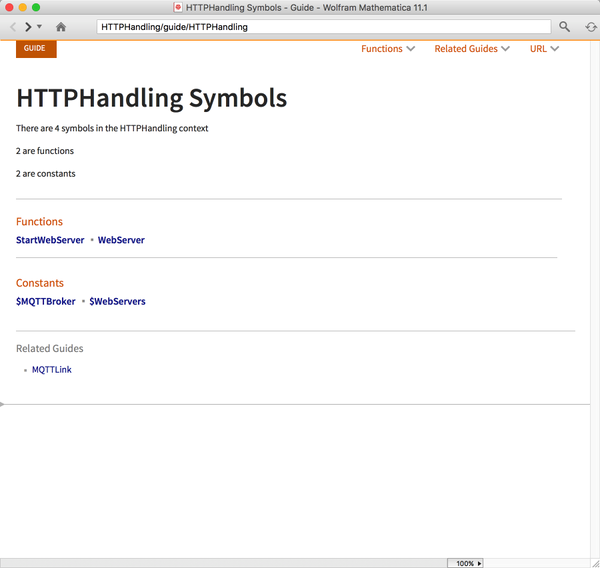

Automatic Context Documentation

Auto-generation becomes most useful when we consider using it to go beyond generating documentation for a single function to something like generating documentation for an entire package or context. For that I wrote a function GenerateDocumentation . It takes a lists of contexts and builds documentation for each that also links to the others. A good example of its utility something like this, where we build documentation for two complementary, undocumented packages:

GenerateDocumentation[{

"MQTTLink`",

"HTTPHandling`"

}]

(*Out:*)

Documentation Deployment

With documentation like this built, we’ll now want some way to make it accessible to others. Here we’ll use the fact that WRI distributes documentation in just such a fashion as HTML pages. We’ll use some of WRI’s tools to build the HTML directly and then distribute this.

Basic HTML Distribution

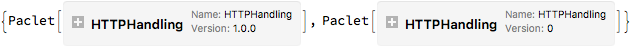

The tools WRI packages require significant correction to get in a useful working order, but I’ve done most of this work myself so that others don’t need to. I packaged it up in a function I called GenerateHTMLDocumentation . Since GenerateDocumentation builds out documentation paclets, we can find these via PacletFind :

PacletFind["HTTPHandling"]

(*Out:*)

We’ll note that one of these has version number 0. That’s the one we want. Version 0 is almost never going to be a release version, so it’s a pretty safe documentation paclet version.

We can then build the HTML docs for a paclet like this and deploy them to the cloud at the same time:

GenerateHTMLDocumentation[PacletFind["HTTPHandling"][[2]],

CloudDeploy -> True] // Replace[#, {c_, ___} :> c, 1] &

(*Out:*)

{CloudObject[

"https://www.wolframcloud.com/objects/b3m2a1.docs/reference/\

HTTPHandling/guide/HTTPHandling.html"], CloudObject[

"https://www.wolframcloud.com/objects/b3m2a1.docs/reference/\

HTTPHandling/ref/StartWebServer.html"], CloudObject[

"https://www.wolframcloud.com/objects/b3m2a1.docs/reference/\

HTTPHandling/ref/WebServer.html"], CloudObject[

"https://www.wolframcloud.com/objects/b3m2a1.docs/reference/\

HTTPHandling/ref/$MQTTBroker.html"], CloudObject[

"https://www.wolframcloud.com/objects/b3m2a1.docs/reference/\

HTTPHandling/ref/$WebServers.html"]}

This is all we need to get the most basic stuff up-and-running.

Building a Documentation Site

On the other hand we may find ourselves wanting more. We might want a general landing page where we can see *all* of our docs. For this, we’ll need to first build out a documentation overview. This process isn’t entirely set-in-stone, so most of the functionality remains in the package scope. But it can demonstrate at least *a* way to do this. Our basic idea will be to take a set of directories, extract what’s known about the documentation they have, and build a landing page for it. The basic call looks like this:

Export[

FileNameJoin@{

BTools`Private`$DocPacletsDirectory,

"Documentation",

"English",

"Guides",

"DocumentationOverview.nb"

},

BTools`Private`Hidden`DocumentationMultiPackageOverviewNotebook[

BTools`Private`$DocPacletsDirectory,

Except@FileBaseName[BTools`Private`$DocPacletsDirectory]

]

]

(*Out:*)

"~/Library/Mathematica/ApplicationData/DocGen/DocPaclets/\

Documentation/English/Guides/DocumentationOverview.nb"

Then we can build and deploy this overview:

GenerateHTMLDocumentation[

BTools`Private`$DocPacletsDirectory,

CloudDeploy -> True

]

(*Out:*)

{

CloudObject[

"https://www.wolframcloud.com/objects/b3m2a1.docs/reference/guide/\

DocumentationOverview.html"]}

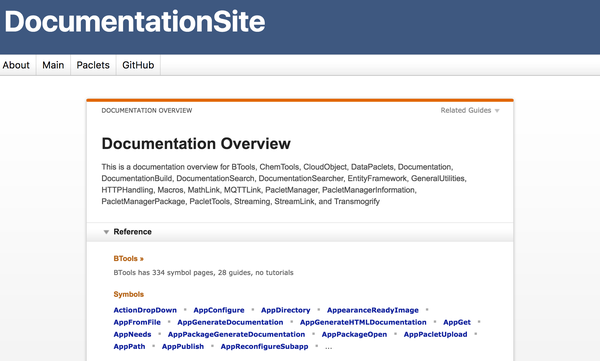

Finally, we’ll build a small wrapper site on top of all of this:

DocumentationSiteBuild["AutoDeploy" -> True];

It uses the same SiteBuilder framework as the paclet site, but the resources are different. Then we go to its main page and we can see why this is useful. It provides us with a way to display our doc pages with extra site info, particularly with links to our paclet site.

Here is a screen shot of the site home:

It is no more than an iframe on that landing page, but it provides a much nicer, more integrated framework. And hopefully all of this together—how automatic it is, how little burden it puts on the user—means we’ll start to see more, easier to use paclets and some development in the Mathematica paclet ecosystem