Better Docs with JHTML

What’s New with JHTML

The last post I wrote was about a framework I had just written allowing rich DOM access through Jupyter widgets.

Since writing that, the framework has grown tremendously, including pretty much every feature one might expect from Bootstrap, including the basic nice formatting things like Cards and Buttons along with richer elements like Carousels, Tabs, Popovers, and Toasts, and layout utilities like Flex and Grid.

This is on top of the richer interactivity that already existed through the use of dynamic variables and functions through the VariableDisplay and FunctionDisplay elements.

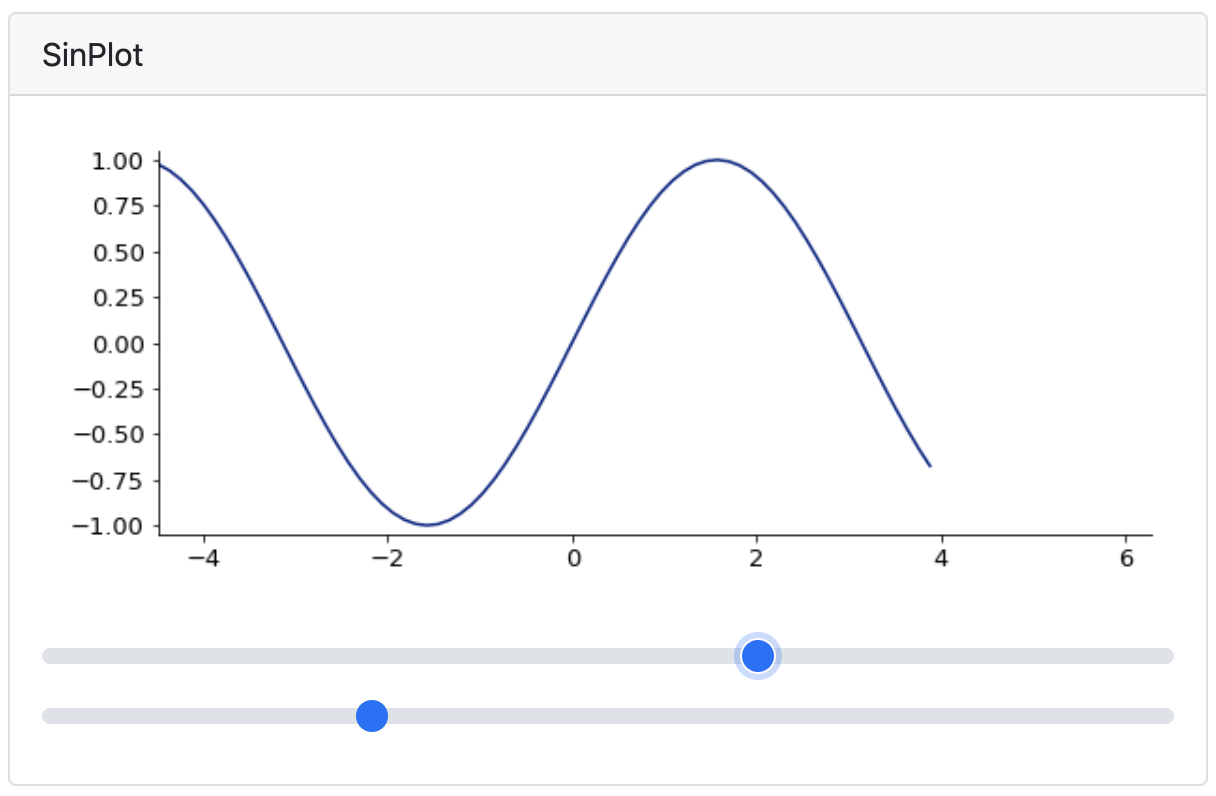

That means it was easy for me to write my own Manipulator object to mimic Mathematica’s Manipulate function.

So now for example we can define a little plotting function

import McUtils.Plots as plt

import numpy as np

def plot_sin(*, x, x_min=-.005, **_):

x_max = x if isinstance(x, (int, float)) else 0

x_min = x_min if isinstance(x_min, (int, float)) else -.005

return plt.Plot(

np.sin,

[x_min, x_max, (x_max-x_min)/70],

plot_range=[[x_min, 2*355/113], [-1.05, 1.05]],

image_size=(600, 250),

)

and we can play with it easily

Manipulator(

plot_sin,

("x", {'range': [0, 2*355/113, .001], 'continuous_update': True}),

("x_min", {'range': [-2*355/113, 0, .001], 'continuous_update': True}),

width='600px',

theme={'output': {'height': '250px'}},

header='SinPlot'

)

HTMLElement(div, (HTMLElement(div, (HTMLElement(div, 'SinPlot', cls=['card-header'], style={}), HTMLElement(di…

and you can play with the parameters just like a regular Manipulate.

Now, there’s certainly room for improvement in this interface, but the fact that it was <25 lines of code to create this completely general Manipulator is a win in my book.

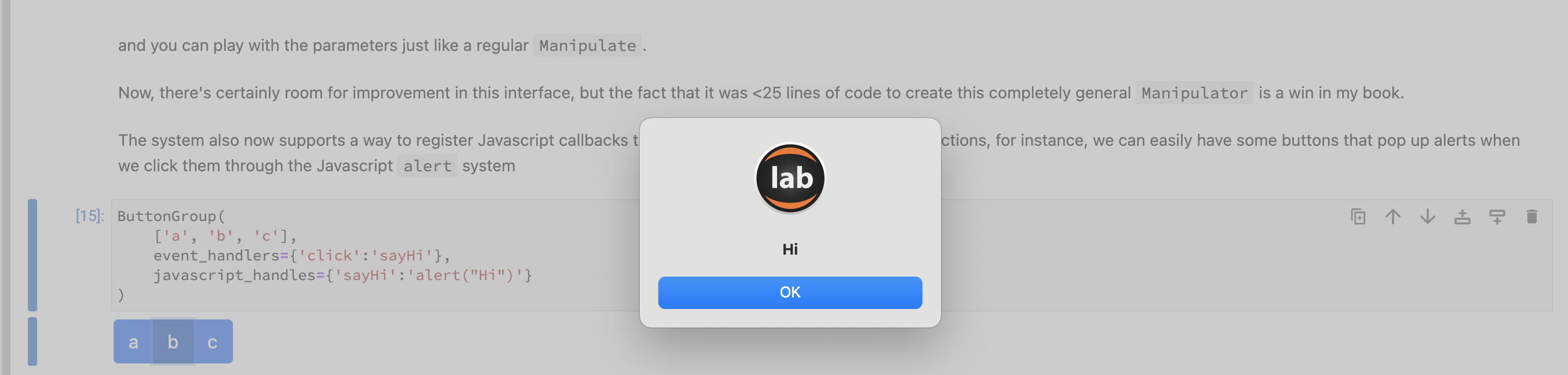

The system also now supports a way to register Javascript callbacks that can be used to get even richer interactions, for instance, we can easily have some buttons that pop up alerts when we click them through the Javascript alert system

ButtonGroup(

['a', 'b', 'c'],

event_handlers={'click':'sayHi'},

javascript_handles={'sayHi':'alert("Hi")'}

)

HTMLElement(div, (HTMLElement(div, (HTMLElement(button, 'a', cls=['btn', 'btn', 'btn-primary'], style={}), HTM…

We can also register handles to fire on events through the onevents keyword. Here’s the same example from above, except now it will fire when the interface element is both initially displayed and when it is removed.

ButtonGroup(

['a', 'b', 'c'],

onevents={'initialize':'sayHi', 'remove':'sayHi'},

javascript_handles={'sayHi':'alert("Hi")'}

)

Or going even further, if we’ve allowed JupyterLab to get out location, we can make a Javascript API to query that

api = JHTML.JavascriptAPI(

nope="""alert(event.content['message'])""",

cb="""

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition((pos)=>this.send({type:'geoloc', pos:[pos.coords.latitude, pos.coords.longitude]}), (e)=>{throw e})

"""

)

where we first query the GeoLocation via navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition and then we can emit a message containing that data by calling this.send({type:'geoloc', pos:[pos.coords.latitude, pos.coords.longitude]}) which will send a geoloc message which we can then listen for with an onevent. This gives us one (but by no means the only) route to get data from the Javascript side–the other reccomended route is to use the data field of a widget which can pass a dict of data, but that’s for another day.

Now we can call our API to get out the location and once the message with it comes in we can handle that message appropriately

with JHTML() as j:

b = JHTML.Bootstrap.Button("Get Location",

event_handlers={"click":"cb", 'geoloc':lambda e,w:print(e['pos'])},

javascript_handles=api

)

d = JHTML.Div(b, j.out)

d

HTMLElement(div, (HTMLElement(div, (HTMLElement(button, 'Get Location', cls=['btn', 'btn-primary'], style={}),…

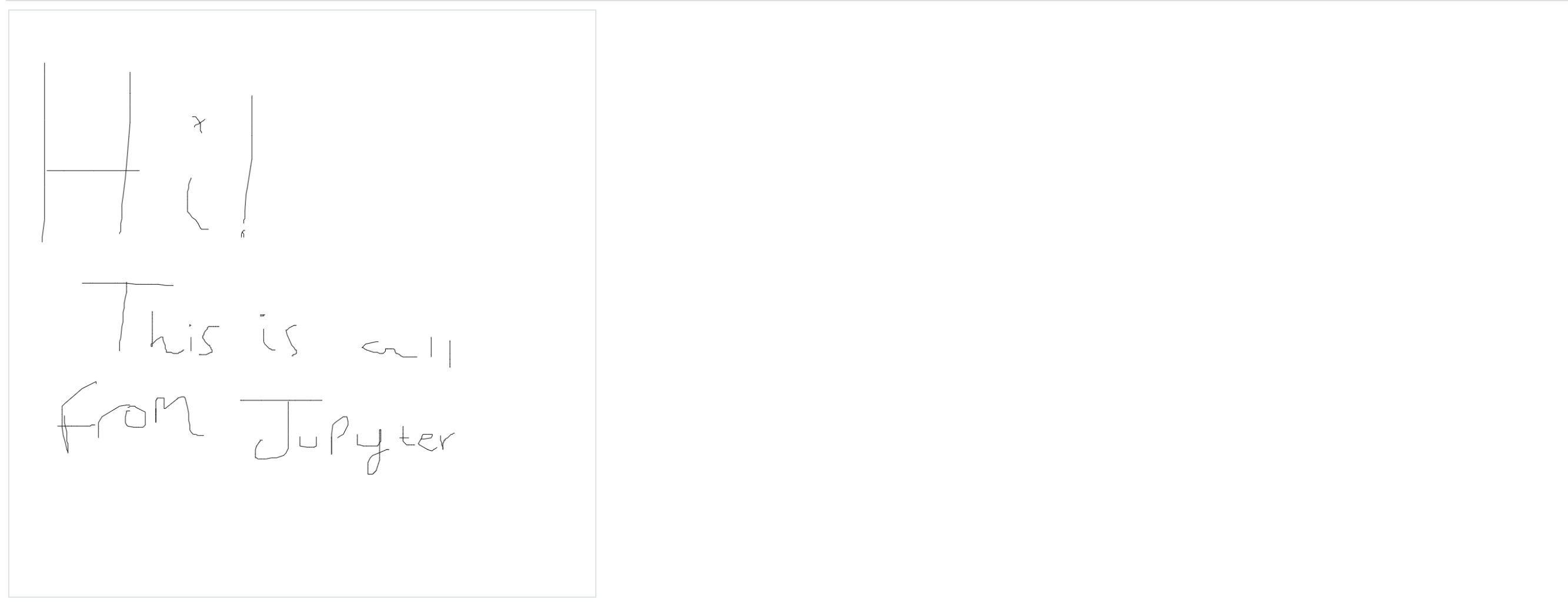

We can do even crazier things, too, like creating an editable Canvas

JHTML.Canvas(

dynamic=True,

width='500px',

height='500px',

cls='border',

id='my-drawing',

onevents={'initialize':'init'},

javascript_handles={

"init":"""

if (!widget.hasOwnProperty('ctx')) {

widget.ctx = widget.el.getContext('2d');

widget.el.width = 1024;

widget.el.height = 1024;

}

""",

"setPosition":"""

widget.pos = { x: event.clientX, y: event.clientY };

let bounds = widget.el.getBoundingClientRect();

// get the mouse coordinates, subtract the canvas top left and any scrolling

widget.pos.x = event.pageX - bounds.left - scrollX;

widget.pos.y = event.pageY - bounds.top - scrollY;

// first normalize the mouse coordinates from 0 to 1 (0,0) top left

// off canvas and (1,1) bottom right by dividing by the bounds width and height

widget.pos.x /= bounds.width;

widget.pos.y /= bounds.height;

// then scale to canvas coordinates by multiplying the normalized coords with the canvas resolution

widget.pos.x *= widget.el.width;

widget.pos.y *= widget.el.height;

""",

"draw":"""

if (event.buttons === 1){

widget.ctx.beginPath();

widget.ctx.moveTo(widget.pos.x, widget.pos.y);

widget.callHandler("setPosition", event);

widget.ctx.lineTo(widget.pos.x, widget.pos.y);

widget.ctx.stroke();

}

"""

},

event_handlers={

'mouseenter':'setPosition',

'mousedown':'setPosition',

'mousemove':'draw'

}

)

HTMLElement(div, (HTMLElement(canvas, '', cls=['border'], style={'width': '500px', 'height': '500px'}),), cls=…

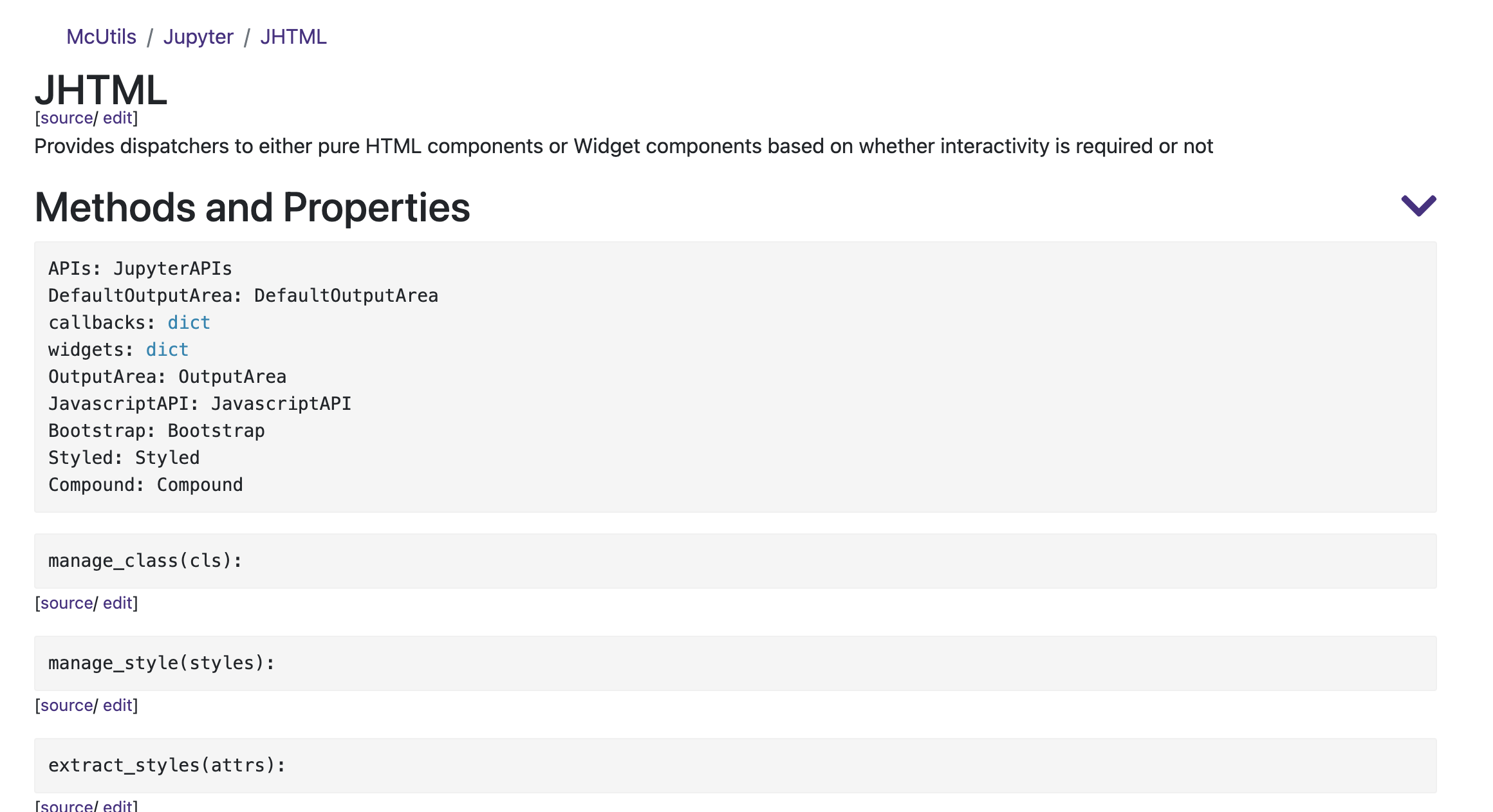

But at some level none of that is particularly useful in my day to day as a scientist and programmer. My real goal with this post was to talk about something that really pays dividends for my work–better documentation.

Documentation Should Thrive in a Notebook

I find writing documentation to be incredibly painful. I think this is partially because I don’t get a quick dopamine hit for making documentation changes and partially because I don’t really use what I write. The benefits all go to a nebulous set of users who I’m not even sure exist as for me it’s just as easy to go into my code base itself as it is to go online to my docs. But by bringing docs into Jupyter, I can hopefully change both of those. This isn’t to say that Jupyter doesn’t already do docs, for example, here’s how it handles learning about JHTML

?JHTML

[0;31mInit signature:[0m

[0mJHTML[0m[0;34m([0m[0;34m[0m

[0;34m[0m [0mcontext[0m[0;34m=[0m[0;32mNone[0m[0;34m,[0m[0;34m[0m

[0;34m[0m [0minclude_bootstrap[0m[0;34m=[0m[0;32mFalse[0m[0;34m,[0m[0;34m[0m

[0;34m[0m [0mexpose_classes[0m[0;34m=[0m[0;32mFalse[0m[0;34m,[0m[0;34m[0m

[0;34m[0m [0moutput_pane[0m[0;34m=[0m[0;32mTrue[0m[0;34m,[0m[0;34m[0m

[0;34m[0m [0mcallbacks[0m[0;34m=[0m[0;32mNone[0m[0;34m,[0m[0;34m[0m

[0;34m[0m [0mwidgets[0m[0;34m=[0m[0;32mNone[0m[0;34m,[0m[0;34m[0m

[0;34m[0m[0;34m)[0m[0;34m[0m[0;34m[0m[0m

[0;31mDocstring:[0m

Provides dispatchers to either pure HTML components or Widget components based on whether interactivity

is required or not

[0;31mFile:[0m ~/Documents/UW/Research/Development/McUtils/McUtils/Jupyter/JHTML/JHTML.py

[0;31mType:[0m type

[0;31mSubclasses:[0m

This isn’t bad, per se, but it could be much better. For contrast, here is what my online docs look like for the same

There’s much more detail and everything is interactable, including source links and (if I’d actually bothered to write them) examples and links to related functions and classes.

The question now is how we bring this to Jupyter.

Extending Peeves.Doc

Happily(?), I rolled my own documentation generator. I didn’t like the docstring format or the appearance of Sphinx docs and figured I knew I’d always want more so I really had to build what I wanted. This is actually a pretty easy task, all told. The necessary ingredients are

- A system for walking through object trees, digging down through modules’ members, classes methods, and so forth

- A docstring parser and resource locator for examples a unit tests

- A formatting system for turning the parsed components into a final format

The first part is very easy to write. The second just requires a standard format. My choice has been to use a Markdown-style docstring but use reStructured text declarations of parameters and parameter types. This format can obviously be tweaked though, since the all of the parsers can be subclassed and reused in the walker object that implements (1). As for part (3), when building for the web I had to write a template engine to generate Markdown docs from .md templates (with some significant extensions to python’s default string.format mechanism). On the other hand, when targeting a Jupyter-style interface I get to use all of my JHTML tricks.

In practice, this means I end up with something that can be displayed directly in the notebook and can be interacted with in a very natural way. For example, documentation for module members is generated on demand, each bit of documentation links to its source, Related functions/classes can be linked to and will replace the current piece of documentation in the active browser, and I’m sure I’ll come up with more.

But before the system was truly a solid replacement for Jupyter’s built-in docstring mechanism I needed one final thing. Jupyter’s docstring printing is called through the ? operator. I wanted my documentation to be accessible via the same. That meant I needed to do a bit of monkey patching though, as the default ? mechanism calls pinfo in the IPython kernel but pinfo supplies no extra hooks that package writers can use. So I wrote a function patch_pinfo that would make it so that pinfo did just that and now whatever is returned from an object’s _ipython_pinfo_ method will be displayed when using ? which means I can do this:

?DocWalker